In Japan, foreign words are almost exclusively written in katakana, one of the country’s three writing systems. Katakana is used to phonetically represent loanwords, technical terms, and the names of foreign people and places. This practice raises intriguing questions: Why is katakana used for foreign words? Where do most loanwords in Japan come from? And how did katakana become the script for these words? This article explores the origins of this practice, which countries influence Japan’s vocabulary the most, and the history of katakana usage.

Why Is Katakana Used for Foreign Words?

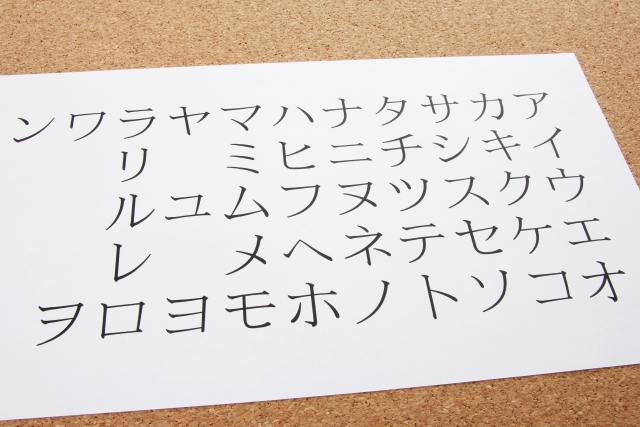

Katakana is one of Japan’s syllabic scripts, primarily used to represent foreign words or names, technical terms, and sometimes for stylistic emphasis. It contrasts with hiragana (used for native Japanese words) and kanji (characters representing meaning). There are several reasons why katakana is used for foreign loanwords:

- Phonetic Representation: Katakana is used to transliterate foreign words phonetically. Since foreign words do not have corresponding kanji (Chinese characters used to represent meaning), katakana provides a way to express the sound of these words using Japanese syllables.

- Clarity and Distinction: Using katakana clearly signals to readers that the word is not native to Japanese. This helps distinguish foreign words from native ones, which might otherwise cause confusion, especially in writing.

- Pragmatic Efficiency: Writing foreign words with kanji would require complex meanings to be assigned to characters, making comprehension difficult. Hiragana, on the other hand, is more associated with native Japanese words and grammatical functions, so using it for foreign terms would blur the line between native and non-native elements of the language.

Historical Context: When Did Katakana Start Being Used?

Katakana emerged in the early Heian period (794–1185) as a shorthand form of Chinese characters. Initially, it was mainly used by monks for annotations in Buddhist texts. By the Meiji era (1868–1912), when Japan opened to Western countries, katakana became the script for transliterating foreign terms. The influx of Western technology, culture, and political ideas prompted the need to incorporate new words into Japanese, and katakana was ideally suited for this task.

Which Countries Contribute the Most Loanwords?

Japan’s loanwords come from various countries, but certain nations have had a particularly strong influence on the Japanese vocabulary. Below is a breakdown by country:

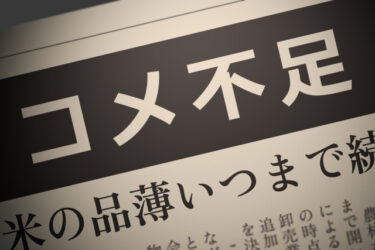

- English: The vast majority of loanwords in modern Japanese are from English. Examples include terms like コンピューター (konpyūtā, computer), インターネット (intānetto, internet), and バス (basu, bus). This trend accelerated after World War II, with the occupation of Japan by U.S. forces and the increasing global dominance of the English language.

- Portuguese: In the 16th century, Portuguese missionaries and traders brought new words to Japan. Some of these, such as パン (pan, bread) and ボタン (botan, button), remain in use today.

- Dutch: During the Edo period (1603–1868), Japan had limited contact with the West, primarily through the Dutch. As a result, medical, scientific, and maritime terms like ガラス (garasu, glass) and ビール (bīru, beer) entered the language.

- German: In the field of medicine, many loanwords come from German due to its influence on Japan’s medical education in the 19th and 20th centuries. Terms like カルテ (karute, medical chart) and メス (mesu, scalpel) reflect this influence.

- French: French has also left its mark, particularly in the areas of cuisine, fashion, and art. Words like アンケート (ankēto, survey) and ビュッフェ (byuffe, buffet) are examples of French loanwords in Japanese.

- Chinese and Korean: Though not written in katakana, many loanwords have also been borrowed from neighboring Asian countries, particularly in historical, cultural, and culinary contexts. These are often written in kanji or hiragana rather than katakana.

Why Not Hiragana?

While katakana is reserved for foreign terms, hiragana is primarily used for native Japanese words and grammatical particles. Hiragana is seen as softer and more traditional, making it better suited for words of Japanese origin or for conveying the nuances of Japanese grammar. Writing foreign words in hiragana would cause confusion, as readers may interpret them as native Japanese words, distorting meaning.

Moreover, katakana’s angular and modern appearance contrasts with the flowing and cursive look of hiragana, which is associated with Japanese identity and traditional texts. Using katakana for loanwords highlights the foreignness of the terms and allows them to stand out in text.

Conclusion

Katakana’s role in representing foreign words in Japan is both practical and historical. From the country’s interactions with Portuguese missionaries in the 16th century to its post-war Westernization, loanwords have become a crucial part of the modern Japanese language. The countries contributing the most loanwords have changed over time, with English now being the dominant source. As Japan continues to evolve and interact with the world, the use of katakana to integrate foreign terms will remain an essential linguistic practice.